All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MDS Alliance.

The mds Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mds Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mds and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MDS content recommended for you

International Consensus Classification of MDS: 2022 updates

The International Consensus Classification (ICC) is an update to the revised fourth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues published in 2016.1 The new ICC of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia, published by Arber et al.2 in Blood, represents a major revision from previous classification systems. Below, we summarize the key points from the ICC, in particular referring to myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). For more information on how this ICC relates to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), check out articles on the AML Hub and the MPN Hub.

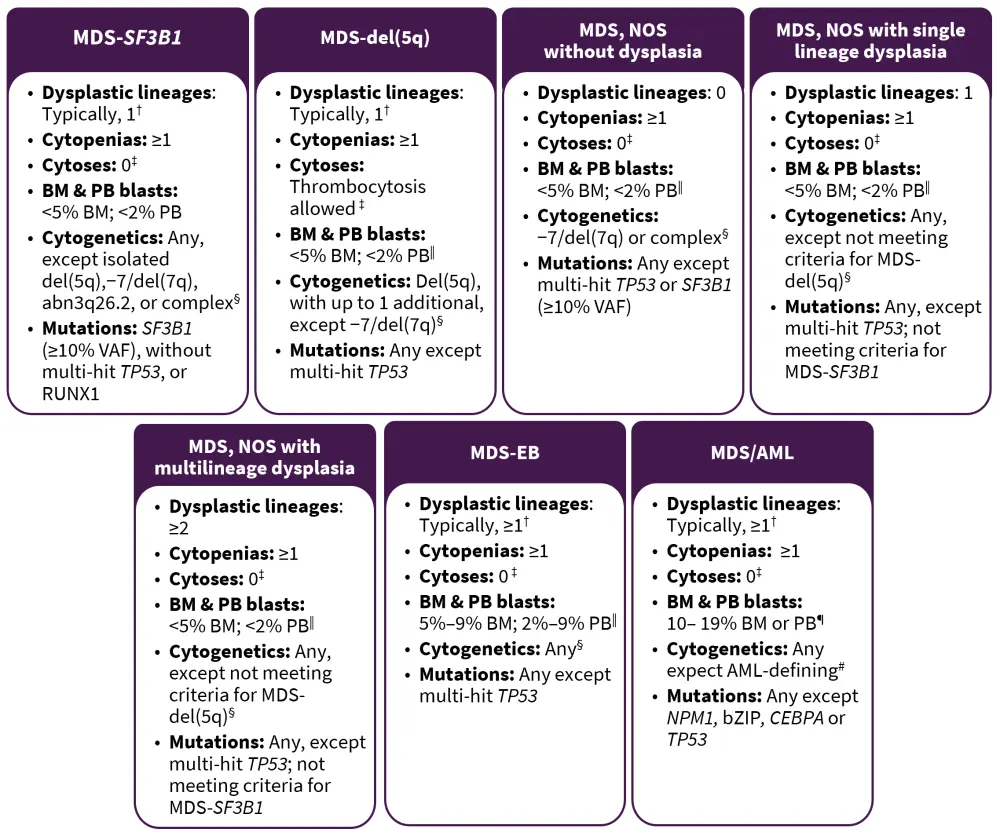

MDS classification2

MDS are defined as clonal hematopoietic neoplasms characterized by persistent unexplained cytopenia and morphologic dysplasia with a propensity to progress to bone marrow (BM) failure or AML. The recommended threshold for defining dysplasia is 10% for all lineages; however, for megakaryocytes, micromegakaryocytes are the most specific indicator of MDS and a higher dysplasia threshold may be warranted when other types of dysmegakaryopoiesis are included. Several genetic abnormalities in the context of persistent cytopenia are still considered to be MDS-defining irrespective of dysplasia (Figure 1).

Subtypes without excess blasts

MDS with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS) has been replaced by MDS with SF3B1 mutations (MDS-SF3B1; Figure 1). In the absence of an SF3B1 mutation, MDS-RS is now classified as MDS not otherwise specified (NOS), irrespective of the number of RS. Single and multilineage dysplasia are retained as subtypes of MDS, NOS. A new MDS subtype is introduced and defined by multi-hit TP53 mutations and the previous category of MDS, unclassifiable has been removed from this ICC. Previous MDS-defining cytogenetic abnormalities in cytopenic patients lacking dysplasia are now classified as clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance (CCUS), except for del(5q), −7/del(7q), or complex karyotype. The presence of 1% peripheral blood (PB) blasts on one occasion is acceptable in any non-excess blast MDS subtype.

The classification of lower-risk MDS has been simplified into three groups, defined by SF3B1 mutations or del(5q), with the remainder in MDS, NOS.

Subtypes with excess blasts

MDS with excess blasts (MDS-EB) is distinguished from lower-risk MDS subtypes by the presence of ≥5% myeloid blasts in the BM or ≥2% blasts in the PB or 1% in PB documented on two occasions (Figure 1). The presence of excess blasts supersedes any of the non-excess blasts MDS subtypes, except MDS with mutated TP53.

MDS/AML

While the blast threshold of 20% defining AML remains, several additional genetic lesions are now considered to be defining AML for myeloid neoplasms with ≥10% BM or blood blasts. The previous category of MDS-EB2 in adults with ≥10% is replaced with MDS/AML, defined as a cytopenic myeloid neoplasm and 10–19% blasts in the blood or BM (Figure 1). Patients with MDS/AML should be eligible for both MDS and AML clinical trials.

Figure 1. MDS subtypes*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; EB, excess blasts; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; NOS, not otherwise specified; PB, peripheral blood; VAF, variant allele frequency.

*Adapted from Arber, et al.2

†Although dysplasia is typically present in these entities, it is not required.

‡Cytoses: sustained white blood count ≥13 × 109/L, monocytosis (≥0.5 × 109/L and ≥10% of leukocytes), or platelets ≥450 × 109/L; thrombocytosis is allowed in MDS-del(5q) or in any MDS case with inv(3) or t(3;3) cytogenetic abnormality.

§BCR::ABL1 rearrangements or any of the rearrangements associated with myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and tyrosine kinase gene fusions exclude a diagnosis of MDS, even in the context of cytopenia.

‖Although 2% PB blasts mandates the classification of an MDS case as MDS-EB, the presence of 1% PB blasts confirmed on two separate occasions also qualifies for MDS-EB.

¶For pediatric patients (<18 years), the blasts threshold for MDS-EB are 5–19% in BM and 2–19% in PB, and the entity MDS/AML does not apply.

#AML-defining cytogenetics are listed in the AML section.

Myeloid neoplasms with mutated TP532

This category includes separate diagnoses of MDS, MDS/AML, and AML with mutated TP53. These entities are grouped together because of their similar aggressive behavior irrespective of the blast percentage. The presence of multi-hit TP53 mutations corresponds to a highly aggressive disease with dismal survival outcomes. The defining criteria for the classification of MDS and MDS/AML with mutated TP53 are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. MDS and MDS/AML with mutated TP53*

|

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; VAF, variant allele frequency. |

|||

|

Type |

Cytopenia |

Blasts |

Genetics |

|---|---|---|---|

|

MDS with mutated TP53 |

Any |

0–9% BM and blood blasts |

Multi-hit TP53 mutations† or TP53 mutations (VAF>10%), and complex karyotype often with loss of 17p‡ |

|

MDS/AML with mutated TP53 |

Any |

10–19% BM or blood blasts |

Any somatic TP53 mutation (VAF >10%) |

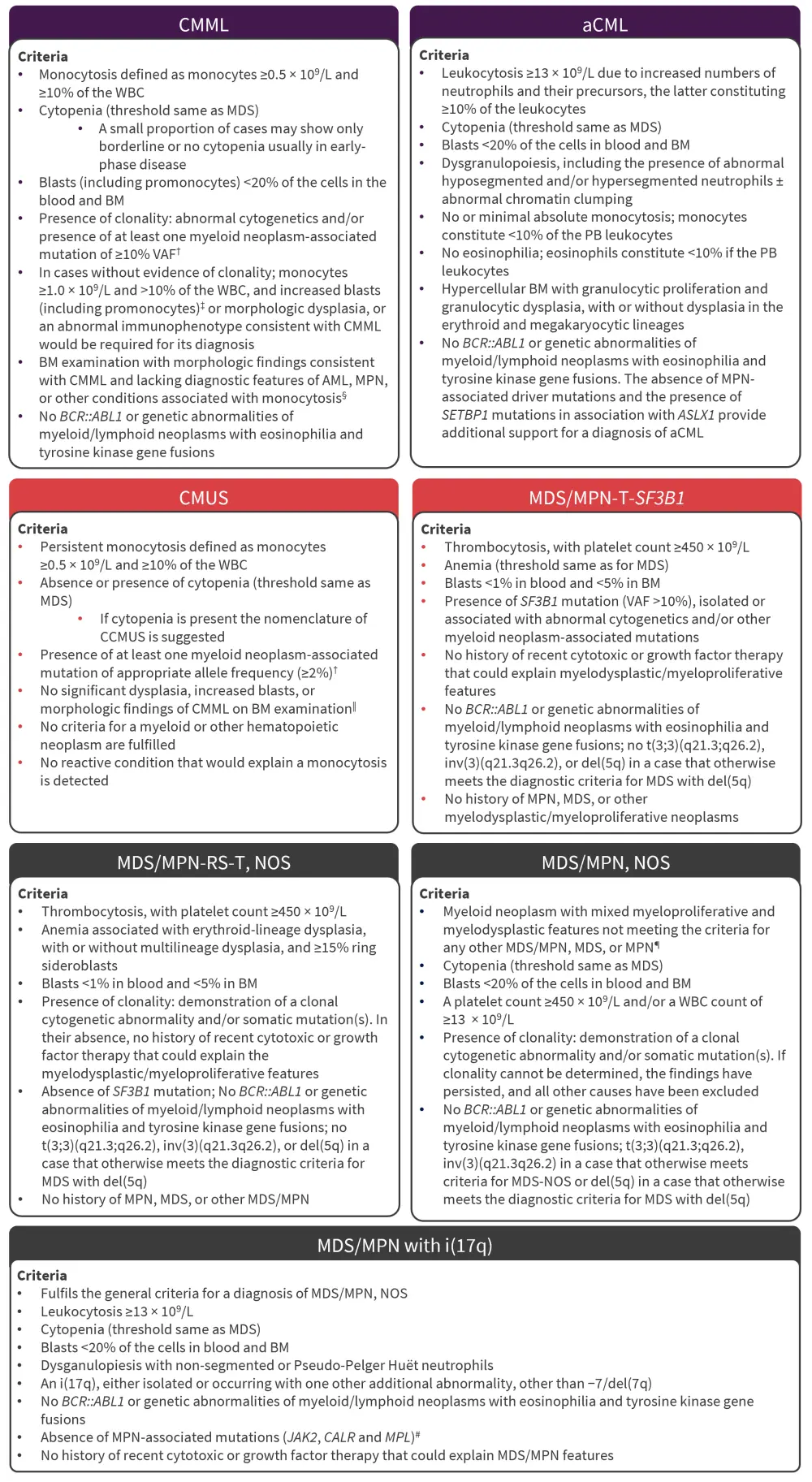

MDS/MPN2

The MDS/MPN category includes a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by the co‑occurrence of clinical and pathologic features of both MDS and MPN. The ICC expands on this group from the fourth edition of the WHO classifications and moves juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia to be grouped with pediatric and/or germline mutation-associated disorders. The major changes in the diagnostic criteria of MDS/MPN are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Diagnostic criteria for MDS/MPN subtypes*

aCML, atypical chronic myeloid leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CCMUS, clonal cytopenia monocytosis of undetermined significance; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CMUS, clonal monocytosis of underdetermined significance; ET, essential thrombocythemia; i(17q), isolated isochromosome (17q); MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms; NOS, not otherwise specified; PB, peripheral blood; PV, polycythemia vera; RS, ring sideroblasts; T, thrombocytosis; VAF, variant allele frequency; WBC, white blood cell.

*Adapted from Arber, et al.2

†Based on International Consensus Group Conference, Vienna, 2018.

‡Increased blasts: ≥5% in the BM and/or ≥2% in the PB.

§For cases lacking bone marrow findings of CMML, a diagnosis of CMUS could be considered. If cytopenia is present, a diagnosis of CCMUS could be entertained. In these diagnostic settings however, an alternative cause for the observed monocytosis would have to be excluded based on appropriate clinicopathologic correlations.

‖Bone marrow findings of CMML include hypercellularity with myeloid predominance, often with increased monocytes and in a proportion of cases monoblasts and/or blast equivalents (ie, promonocytes) and/or dysplasia in ≥1 lineage.

¶MPN, particularly those in accelerated phase and/or post-PV or post-ET myelofibrotic stage, may simulate MDS/MPN, NOS. A history of MPN and/or the presence of MPN-associated mutations (in JAK2, CALR, or MPL) particularly if associated with a high VAF tend to exclude a diagnosis of MDS/MPN, NOS. The presence of hypereosinophilia would favor a diagnosis of chronic eosinophilic leukemia, NOS.

#Presence of MPN features in the bone marrow and/or MPN-associated mutations (in JAK2, CALR, or MPL) suggests the progression of an underlying MPN that was not diagnosed and should be excluded; conversely, in the appropriate clinical context, mutations particularly co-mutations in SRSF2 and SETBP1 genes further support this diagnosis.

Disease progression2

The premalignant clonal cytopenias CCUS, aplastic anemia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic (VEXAS) syndrome can progress to MDS once dysplasia, excess blasts, or MDS-defining genetic lesions occur. Any non-excess blast MDS subtype can progress to MDS-EB, MDS/AML, or AML, and MDS-EB can progress to MDS/AML or AML depending on blast count. Similarly, if a TP53 mutation develops, MDS can progress to MDS, MDS/AML, or AML with mutated TP53. MDS-SF3B1 with the later development of thrombocytosis is no longer reclassified as MDS/MPN. The development of leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, or monocytosis does not require a reclassification from MDS to MDS/MPN.

Diagnostic qualifiers2

All therapy-related MDS cases should be qualified with a “therapy-related” statement after the diagnosis, with the priority to classify based on morphological and genetic features. Any underlying germline predisposition mutation or syndrome should be included as a qualifier after the MDS diagnosis and subtype.

Conclusion

It is worth noting the WHO also published a fifth edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms in 2022.3 While there are many similarities between the two classification systems, there are also some key differences.4 For example, the WHO fifth edition retains MDS-EB2, while the ICC replaces this entity with MDS/AML.4 The differences between the classification systems may lead to confusion for clinicians and patients, which raises the need for harmony between the classification system and a common language.4

Overall, the updates in this ICC represent the advancements in the understanding of MDS, backed by clinical experience and data from clinical trials.1 These updates can be helpful in improving the diagnosis and prognostication of patients with MDS with distinguished subtypes.2 This ICC emphasized genetic factors, reflecting the impact of these factors on the prognosis of MDS.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content