All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MDS Alliance.

The mds Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mds Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mds and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MDS content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Genetic pathogenesis of MDS: Translating molecular advances into better diagnosis and prognosis of CCUS and MDS

Featured:

The last 30 years of advances in molecular biology and high-throughput techniques have significantly impacted the diagnosis, prognosis, and development of targeted-therapy for hematologic malignancies. Relevant breakthroughs have been reported in treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia, B-cell lymphomas, and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), associated with the discovery of targetable disease-defining mutations.1

Similarly, in the myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) field, there has been an enormous effort to better understand its heterogeneous molecular pathogenesis and identify frequent karyotype and genetic variations, which have yet to be translated into clinical improvements.1

In our first Editorial Theme, the MDS Hub will share some recent and relevant reported endeavors to implement molecular genetic analysis in the diagnosis, risk assessment, and clinical management of patients with MDS.

During the 62nd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition, Constance Baer and colleagues presented a study using different levels of analysis (morphology, karyotype, and DNA sequence) to evaluate cytopenic patients.2 Here, we summarize their findings. Look out for more articles coming soon on our Editorial theme: Genetic pathogenesis of MDS.

Study design2

This study included 576 patients visiting the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory requiring a bone marrow biopsy for a differential diagnosis of MDS. All samples were analyzed according to:

- Cell morphology

- Cytogenetics

- Gene expression and variant classification

Incorporating a 41-gene panel to study gene expression, the investigators aimed to:

- Identify new mutations that may help define a subgroup of patients that could benefit the most from a specific therapy strategy, e.g., SF3B1 mutation and luspatercept.

- Identify clonal patterns in the disease's continuous evolution from clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance (CCUS), through MDS, to secondary AML (although not all patients experience all phases). This could become a new progression-risk stratification tool to guide personalized treatment decisions at earlier stages of the disease.

Results2

A bone marrow biopsy was performed in 221 female and 355 male patients with a median age of 72 years (range, 17–94). If any hematologic malignancy other than CCUS or MDS was diagnosed, the patient was excluded from this study.

Mutational analysis

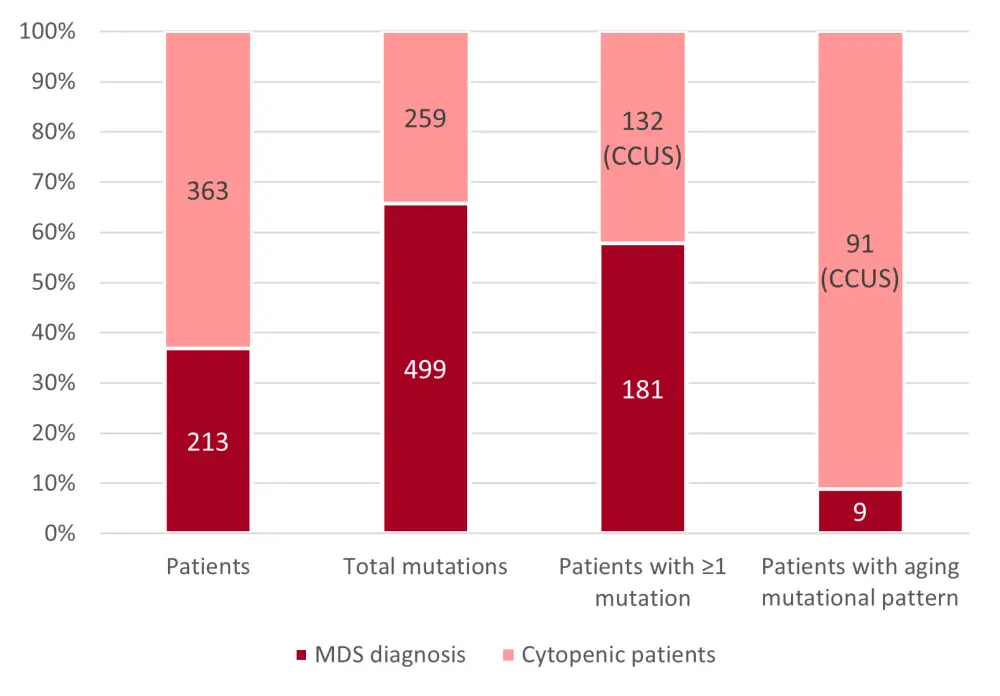

A total of 213 patients included in this analysis were diagnosed with MDS. Of those, 85% of patients presented with one or more mutations (some cases harboring even more than five mutations).

In the remaining 363 cytopenic patients, 36% harbored ≥1 mutation, and consequently were diagnosed with CCUS. Overall, the total number of mutations detected was significantly lower on average in the CCUS subgroup than in the MDS cohort (2.0 vs 2.8, p < 0.01).

Patients with CCUS also presented more frequently with the aging pattern (25% vs 4%, p < 0.01), defined as the presence of a variant allele frequency (VAF) > 10% for mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 (DTA) when no other mutation is present (Figure 1).

Cytopenic patients without any detectable mutation were diagnosed with idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance, ICUS, and interestingly, they were significantly younger than the other two subgroups (median age: 66 years in ICUS vs 75 years in MDS vs 74 years in CCUS, p < 0.02).

Figure 1. Patient distribution according to mutational analysis and diagnosis2

Exploring mutation-driven treatment2

The investigators established three possible mutation-based cohorts that would require different treatment approaches:

- Patients harboring at least one high-risk mutation (TP53, CBL, EZH2, RUNX1, U2AF1, and ASXL1),3 who could be evaluated for an allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

- Patients with SF3B1 mutations, who could be treated with luspatercept.

- Patients with other mutations with currently available targeted therapies (i.e., CSNK1A1, FLT3, IDH1, IDH2, KRAS, and NRAS.

More than 50% of patients with MDS could be classified in one of these cohorts, mostly in the high-risk group 1 (45%). Of note, some patients with CCUS could also be classified by this system, and again, the high-risk subgroup was the larger group (28%). Hence, the authors confirm that some high-risk mutations can be identified before the disease progresses to MDS.2

Regarding group 2, the International Working Group for MDS prognosis recently published the criteria that identify this subgroup as a distinct entity. Patients with SF3B1-mutant MDS typically present with ineffective erythropoiesis, a relatively good prognosis, and anemia sensitive to luspatercept.4 In this study, 12% of patients with MDS presented with SF3B1 mutations. Interestingly, these mutations were also detectable in this CCUS cohort, in 5% of patients, meaning that according to the cited guidelines, these patients could be treated as MDS, even without the diagnostic morphologic features.

Patients classified in group 3 represented 6% and 3% of the MDS and CCUS cohorts, respectively.

Finally, Constance Baer discussed data obtained by Malcovati et al. in 2017 – the highly specific molecular pattern for myeloid malignancies, which identifies cytopenic patients with a 20% risk to develop a myeloid malignancy per year. A total of 65 patients diagnosed with CCUS also present with this highly specific molecular pattern, frequently found in MDS, before meeting current morphological or cytogenetic MDS diagnostic criteria.

Conclusion

Despite being less common, MDS-related mutations can also be identified in patients with cytopenia. In this study, two-thirds of MDS patients and one-third of CCUS patients had mutations that would independently indicate personalized or risk-adapted treatment. Identifying these highly specific mutations could help in treatment decisions at an earlier stage of disease and throughout the treatment continuum, based on every patient's specific risk.

Additionally, this study consolidates molecular genetics as a crucial emerging tool to assess cytopenic patients, together with morphology and cytogenetics. Listen below to Uwe Platzbecker advocating for implementation of these techniques for an improved prognostic assessment of patients.

Expert Opinion

Uwe Platzbecker

Uwe PlatzbeckerReferences

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content