All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MDS Alliance.

The mds Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mds Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mds and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MDS content recommended for you

Venetoclax with intensive chemotherapy for younger patients with ND AML, or MDS

Intensive chemotherapy regimens have been the mainstay of newly diagnosed (ND) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) induction therapy for several decades. During this time, alterations to the standard backbone therapy have yielded improved response rates, longer remissions, and improved survival in those who are fit and <60 years. Such regimens include the CLIA regimen (cladribine with higher dose cytarabine and idarubicin) which has been shown to achieve high complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) rates in a small study of patients with a mean age of 54.1 Further, the addition of the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax, improves CR and PR rates in older patients (≥75 years) or unfit patients treated with a lower intensity treatment regimen using hypomethylating agents (HMA).1

In their recent Lancet Haematology publication, Kadia et al.1 reported on the safety and activity of venetoclax in combination with CLIA in younger patients (<65 years old) with AML, which we summarize here.

Study design

- Single center, single-arm cohort study (independent cohort added to a larger phase II trial; NCT02115295)

- Included patients were 18–65 years old, had ND AML, mixed phenotype acute leukemia, or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤2, and had not previously received potentially curative therapy for leukemia

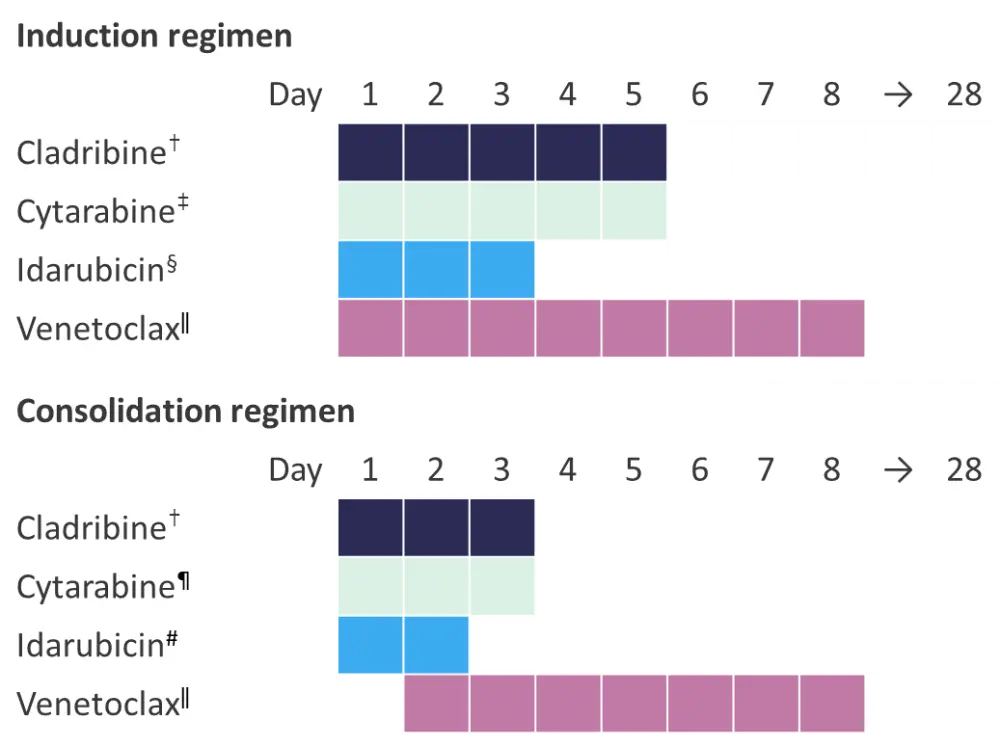

- Treatment regimens are detailed in Figure 1

- Primary outcome: Composite CR or a CR with incomplete blood count recovery (according to the modified International Working Group criteria; measured from Day 1 until the absolute neutrophil count was ≥1,000 cells per μL, platelet count was ≥50,000 platelets per μL, or both)

- Secondary and exploratory outcomes: Overall response rate, overall survival (OS), event-free survival (EFS), duration of response, safety, and OS and EFS stratified by concomitant FLT3 inhibitor receipt and measurable residual disease (MRD) status.

Figure 1. Induction and consolidation treatment regimens*

*Adapted from Kadia et al.1

†Intravenously (IV), 5 mg/m2.

‡IV, 1.5 g/m2 in patients aged >60 years, 1 g/m2 in patients aged ≥60 years.

§IV, 10 mgm2.

ǁ400 mg.

¶IV, 1 g/m2 in patients aged <60 years, 0.75 g/m2 in patients aged ≥60 years.

#IV, 8 mg/m2.

Eligible patients in first complete response were offered allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Treatment could continue for up to six courses.

Results

Patients (N = 50) had a median age of 48, were mostly male (56%) with AML (90%), and 50% had a diploid karyotype (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics*

|

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ELN, European Leukemia Network; IQR, interquartile range; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes. |

|

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

Patients |

|---|---|

|

Median age, years (IQR) |

48 (37–56) |

|

Race or ethnicity |

|

|

White |

60 |

|

Black |

20 |

|

Asian |

4 |

|

Hispanic |

2 |

|

Other |

14 |

|

Sex |

|

|

Female |

44 |

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

AML |

90 |

|

MDS |

8 |

|

Mixed phenotype acute leukemia |

2 |

|

Cytogenetic group |

|

|

Favorable |

2 |

|

Diploid |

50 |

|

Other intermediate |

16 |

|

Adverse of complex |

20 |

|

Insufficient mitoses |

10 |

Kadia et al.1 reported a composite CR in 94% of patients, which included a CR in 84% and CR with incomplete blood count in 10% of patients (Table 2). Of the 45 patients eligible for assessment, 82% achieved MRD negativity during the course of the study. Median OS and EFS were not reached over a median follow-up of 13.5 months, the estimated 12-month OS was 85% (95% confidence interval [CI], 75–97), and estimated 12-month EFS was 68% (95% CI, 54–85; Table 2). There were two patients who did not respond.

Table 2. Patient response*

|

Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; CI, confidence interval; CLIA, cladribine, high dose cytarabine, and idarubicin; CR, complete response; EFS, event-free survival; IQR, interquartile range; MRD, measurable residual disease; OS, overall survival. |

|||

|

Outcome, % (95% CI) unless otherwise stated |

Overall |

CLIA plus venetoclax |

CLIA plus venetoclax plus FLT3 inhibitor |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Composite CR |

94 (83–98) |

95 (84–99) |

89 (56–99) |

|

Best response |

|||

|

CR |

84 (72–92) |

85 (72–93) |

78 (45–94) |

|

CR with incomplete blood count |

10 (4–21) |

10 (4–23) |

11 (2–44) |

|

No response |

4 (1–14) |

5 (1–16) |

0 (0–30) |

|

Died during induction |

2 (0–11) |

0 (0–9) |

11 (2–43) |

|

MRD-negative after induction |

71 (57–82) |

72 (56–83) |

50 (22–78) |

|

MRD-negative on study |

82 (68–92) |

94 (72–94) |

62 (31–86) |

|

Median number of courses given (IQR) |

2 (2–3) |

2 (2–3) |

2 (1–2) |

|

Median days to count recovery after induction (IQR) |

27 (25–37) |

27 (25–31) |

38 (34–40) |

|

Responders who received allo-HSCT |

62 (47–74) |

60 (43–73) |

75 (41–93) |

|

12-month OS |

85 (75–97)† |

90 (80–100) |

64 (38–100) |

|

12-month EFS |

68 (54–85)† |

73 (58–92) |

51 (26–100) |

|

12-month duration of response |

74 (60–92)† |

— |

— |

Overall, the most frequently reported Grade 3–4 adverse events were febrile neutropenia (84% of patients), infection (12%), and raised alanine aminotransferase (12%). Adverse events by treatment course are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Most common adverse events*†

|

ALT, alanine aminotransferase elevation; AST, aspartate aminotransferase elevation. |

|||

|

Adverse event, % |

Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3–4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

During the first treatment course (N = 50) |

|||

|

ALT elevation |

46 |

12 |

10 |

|

AST elevation |

12 |

0 |

4 |

|

Bilirubin elevation |

4 |

4 |

2 |

|

Cough |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Diarrhea |

22 |

0 |

4 |

|

Fatigue |

54 |

0 |

0 |

|

Febrile neutropenia |

0 |

0 |

78 |

|

Mucositis |

32 |

2 |

0 |

|

Nausea |

26 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pain |

22 |

0 |

0 |

|

Rash or desquamation |

26 |

0 |

2 |

|

During the second treatment course (n = 44) |

|||

|

ALT elevation |

9 |

2 |

16 |

|

Cough |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Diarrhea |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Fatigue |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Febrile neutropenia |

0 |

0 |

36 |

|

Other infection |

2 |

0 |

11 |

|

Nausea |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Pain |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Petechiae, purpura or bruising |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Vomiting |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

During the third treatment course (n = 18) |

|||

|

Febrile neutropenia |

0 |

0 |

11 |

Three patients who received CLIA died during the study; one from bacteremia and sepsis during induction, and two from infectious complications whilst cytopenic. None were deemed treatment related.

Conclusion

The addition of venetoclax to the CLIA high intensity chemotherapy regimen resulted in durable CRs in patients with ND AML and high-risk MDS, with high rates of MRD-negativity. The authors considered that these data compared favorably with other published studies in similar patient groups without venetoclax. However, they cautioned against drawing cross-trial comparisons, highlighting the single center, single arm nature of this study as a limitation, alongside the small subgroup numbers. Nonetheless, they concluded that the study was a basis for future randomized controlled trials to confirm the potential benefit that venetoclax plus CLIA may offer to younger, fit, ND AML patients.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content