All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MDS Alliance.

The mds Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mds Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mds and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MDS content recommended for you

Updates from #ASCO23 and EHA on the efficacy and safety of ivosidenib, including molecular characterization and long-term follow-up in patients with mutant IDH1 AML and R/R MDS

Somatic mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) are less common in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) but are associated with poor survival outcomes. Ivosidenib, a potent oral targeted inhibitor of mutant IDH1 (mIDH1), has demonstrated durable responses in early-phase studies.1–4 Ivosidenib has recently been approved by the European Commission for the treatment of adult patients with IDH1-mutated (mIDH1) AML, and there is also an interest in ivosidenib for the treatment of mIDH1 MDS.

During the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Meeting 2023 and the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2023 Congress, updates were presented on ivosidenib for the treatment of MDS and AML. We are pleased to summarize three presentations: Courtney DiNardo presented results from a phase I substudy of ivosidenib in patients with mIDH1 relapsed/refractory (R/R) MDS1; Justin Watts and Eytan Stein presented data on the molecular characteristics and duration of response among exceptional responders of ivosidenib2,3; and Stephane de Botton presented an update from the AGILE study.4

Ivosidenib in mIDH1 relapsed/refractory MDS1

A substudy analysis from a phase I ivosidenib trial (NCT02074839) in patients with mIDH1 hematologic malignancies, found encouraging results in the 12 patients with R/R MDS who had received 500 mg ivosidenib once daily. Based on these efficacy and safety data, additional patients with R/R MDS were enrolled. The primary endpoints were safety, tolerability, and clinical activity (complete [CR] and partial response [PR]).

In total, 19 patients were included, with a median age of 73 years. Of these patients, 78.9% were male. An International Prognostic Scoring System score of >3 was observed in 73.1% of patients at screening. The median duration of treatment was 9.26 months (range, 3.3–78.8 months). Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurred in 42.1% of patients and serious TRAES in 15.8% of patients; however, no TRAEs led to treatment discontinuation. There were two patients who discontinued treatment due to treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs); however, these were not considered to be TRAEs. Among patients with TRAEs, two experienced Grade 2 differentiation syndrome and one experienced Grade 2 skin infection.

CR and ORR were achieved by 38.9% and 83.3% of the 18 evaluable patients. Marrow CR (mCR) was achieved by 44.4% of patients, and of those, 50% had hematologic improvement in ≥1 lineage. All patients (n = 9) with the R132C variant experienced either CR or mCR. Transfusion independence (TI) was achieved by 71.4% and 75% of patients who were red blood cell or platelet dependent, respectively, at baseline, and 81.8% and 100% continued to have TI at data cut-off.

ASXL1 and SRSF2 were the most common co-mutations identified and were found in eight patients each. CR or mCR was achieved by eight and six patients with SRSF2 and ASXL1 co-mutations respectively. The two patients with TP53 mutations achieved CR and mCR and had a duration of response (DoR) of 65.3 and 70.9 months, respectively.

Presenter’s conclusion

This subset analysis demonstrated that ivosidenib induced durable responses in patients with mIDH1 R/R MDS, with TRAEs not resulting in treatment discontinuation. A high proportion of patients remained transfusion independent, providing an effective treatment option for this molecularly defined population.

Exceptional responders of ivosidenib2,3

In another subset analysis of the same phase I study of ivosidenib (NCT02074839), patients with mIDH1 R/R AML who received 500 mg ivosidenib once daily and had achieved CR or CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh) for >12 months were analyzed (n = 20).

Of the 20 patients considered exceptional responders, seven were excluded as they had received a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Of the 13 patients remaining, 23.1% patients were aged >75 years and 30.8% patients had at least two prior lines of therapy. The median duration of response (DoR) was 42.6 months, and median OS was not reached in these exceptional responders. The estimated OS was 67.1% at 48 months, and the median event-free survival was 44.4 months. Five of 13 patients relapsed: 4 patients within 12–24 months and 1 patient after 31 months. DNMT3A, ASXL1, SRSF2, and JAK2 were the most common co-mutations identified in the exceptional responders. Five patients had a splicing factor mutation, and no patient had FLT3 or RTK pathway mutations. One patient with NPM1 had an exceptional response, and one patient had a TP53 (variant allele frequency [VAF] 3.6%) mutation. IDH1 R132C mutation was present in 11 patients.

Exceptional responders with 0–1 co-mutations (n=7) had a longer DoR (median DoR was not reached) compared with those with >1 co-mutation (n = 6; DoR 15 months). The median number of co-mutations was 1 (range, 0–6) and the median mIDH1 variant allele frequency (VAF) was 25% (range, 10–50%). Most exceptional responders (61.5%) achieved mutation clearance (VAF <0.02–0.04%), though three patients had persistent VAF of <1%, and 2 patients had persistent VAF ≥1%.

Presenter’s conclusion

This subset analysis of exceptional responders to ivosidenib demonstrates that a low mutation burden, absence of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) pathway mutations and AML-defining drivers, and co-occurrence of clonal hematopoiesis mutations was associated with the exceptional response. Progressive reduction in mIDH1 VAF was also associated with a sustained response.

Update on efficacy and safety of ivosidenib – AGILE study4

This is a global, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial (NCT03173248) in patients with newly diagnosed mIDH1 AML who are ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy. Patients received either 500 mg ivosidenib or placebo once daily, plus azacitidine (AZA) 75 mg/m2 for 7 days in a 28-day cycle. The updated analysis focused on the long-term follow-up from the AGILE study on OS, TI, blood count recovery, and safety.

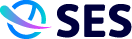

Overall, 73 and 75 patients were included in the ivosidenib + AZA and placebo + AZA arms, respectively. At a median follow-up of 28.6 months, median OS with ivosidenib + AZA was superior to placebo + AZA (29.3 months [95% CI, 13.2–not reached] versus 7.9 months [95%CI, 4.1–11.3]; hazard ratio [HR], 0.42; p < 0.001). OS rates at 12, 24, and 36 months are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overall survival rates*

AZA, azacitidine.

*Adapted from S. de Botton.4

Deaths were reported in 50.7% and 77.3% of patients in the ivosidenib + AZA versus placebo + AZA arm, respectively.

Hemoglobin, platelet, and neutrophil levels recovered and stabilized during treatment with ivosidenib + AZA. Hemoglobin levels increased from baseline (88.8 g/L) to Cycle 8 before stabilizing. Mean platelet count increased from baseline (72.7 x 109/L) to Week 8 (171.9 x 109/L) after which it remained stable. Mean neutrophil counts also increased from baseline (0.98 x 109/L) to Week 4 (4.36 x 109/L) then continued to stabilize to within the normal range.

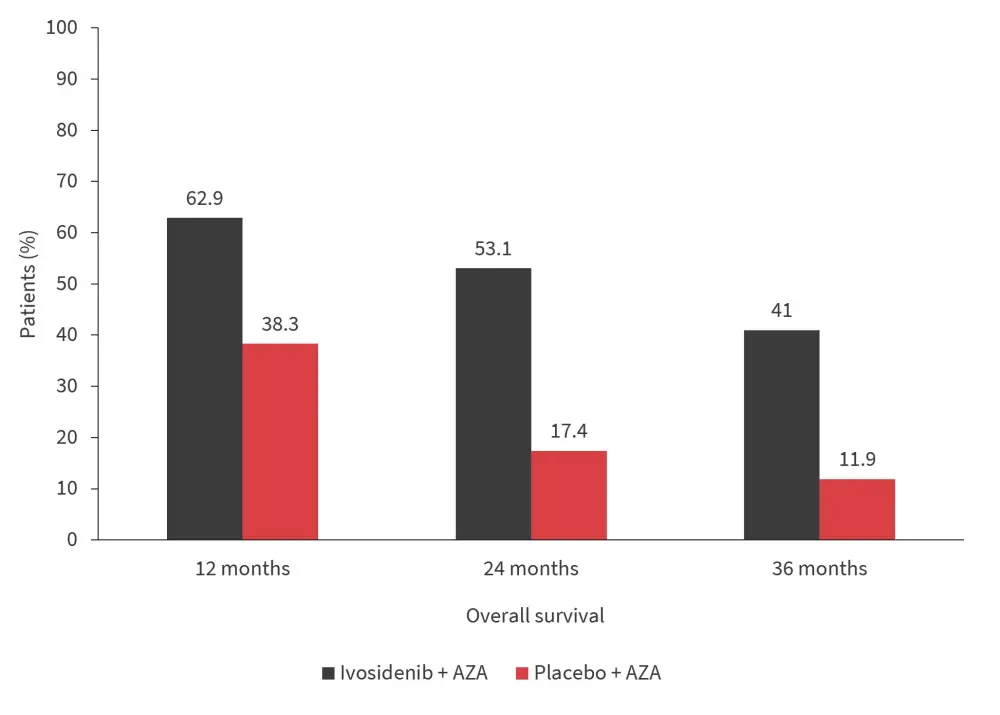

In addition, patients in the ivosidenib + AZA arm achieved a higher rate of TI compared with placebo (Figure 2). TI was also maintained in 70.6% of patients in the ivosidenib + AZA arm.

Figure 2. Transfusion independence*

AZA, azacitidine; RBC, red blood cell.

*Adapted from S. de Botton.4

†Transfusion independence was defined as a period of at least 56 days with no transfusion after the start of study treatment and on or before the end of study treatment + 28 days, or disease progression, or confirmed relapse, or death or data cut-off, whichever is earlier.

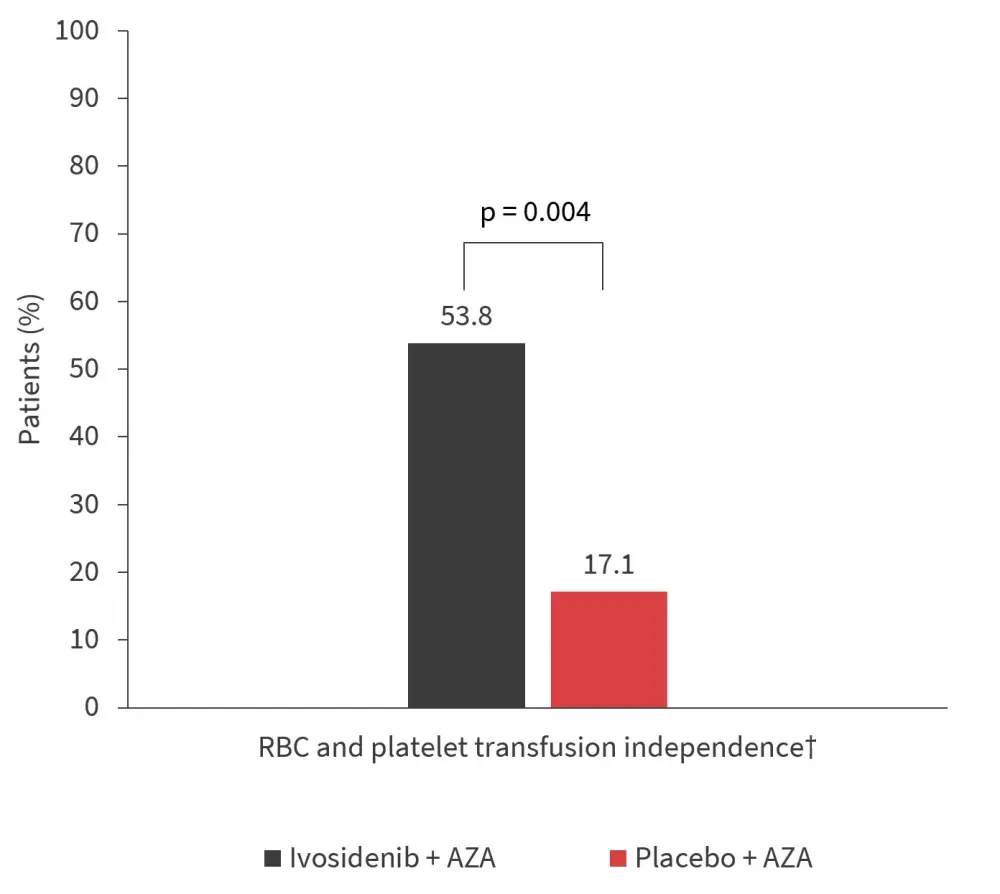

Patients in the ivosidenib + AZA arm did not show a significant increase in hematological adverse events. Fewer febrile neutropenia events occurred in the ivosidenib + AZA arm versus placebo + AZA arm (Figure 3). Grade ≥3 TEAEs occurred in 91.7% and 95.9% of patients in ivosidenib + AZA versus placebo + AZA arm. TEAEs led to dose reduction in 18.1% and 8.1% and treatment discontinuation in 26.4% and 25.7% of patients in ivosidenib + AZA versus placebo + AZA arm, respectively. Any-grade pneumonia (23.6% vs 32.4%), and infections (34.7% vs 51.4%), as well as Grade ≥3 pneumonia (22.2% vs 29.7%) and infection (22.2% vs 31.1%) were less frequent in the ivosidenib + AZA versus the placebo + AZA arm.

Figure 3. Hematological AEs*

AE, adverse event; AZA, azacitidine.

*Adapted from S. de Botton.4

Presenter’s conclusion

The long-term follow-up data from the AGILE study supports the efficacy and safety of ivosidenib + AZA versus placebo + AZA in patients with newly diagnosed mIDH1 AML. Hematologic recovery and TI achieved by ivosidenib + AZA further supports its clinical benefit.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content