All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MDS Alliance.

The mds Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mds Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mds and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MDS content recommended for you

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation vs 5-azacytidine treatment in elderly patients with high risk MDS

Your opinion matters

Will HMA pre-treatment improve survival before allo-HSCT in elderly MDS patients? A - Yes B - No C - Others (option for explanation)

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a diverse group of clonal hematologic disorders that result in cytopenias and can potentially progress to acute leukemia. Currently, allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) is considered a curative treatment strategy for patients with MDS, though therapy-related mortality (TRM) has limited its widespread use in elderly patients with MDS. Use of hypomethylating agents such as 5-azacytidine (5-aza), a DNA-methyltransferase inhibitor, prior to allogeneic HSCT has reportedly been effective but can enhance the graft-versus-leukemia or myelodysplasia effect.

In a recent study, Kroger, et al. compared allogeneic reduced-intensity conditioning HSCT after pre-treatment with 5-aza and continuous 5-aza therapy in older patients with MDS to evaluate improvement in patient survival.

Study design and patient enrolment

Patients (age range, 55–70 years) with de novo or therapy related MDS or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia were included. Table 1 presents patient characteristics at the time of enrollment and after pre-treatment with 5-aza (when patients were allocated to respective cohorts but prior to allogeneic stem-cell transplantation or continuous 5-aza treatment).

Table 1. Patient characteristics at study entry and after four pre-treatment cycles of 5-aza*

|

5-aza, 5-azacytidine; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; IPSS-R, international prognostic scoring system-refined; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; PR, partial response; RAEB, refractory anemia with excess of blasts; RAEB-T, refractory anemia with excess of blasts in transformation, SD, stable disease. |

|||

|

Variable, n (unless otherwise stated) |

At the start of 5-aza treatment (n = 162) |

After 4 pre-treatment cycles with 5-aza |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

HSCT (n = 81) |

Continuous 5-aza (n = 27) |

||

|

Median age (range), years |

63 (55–70) |

63 (55–70) |

65 (55–72) |

|

Male |

100 |

56 |

10 |

|

Disease classification |

|

|

|

|

MDS |

125 |

66 |

18 |

|

RAEB 1/2 |

105 |

60 |

15 |

|

AML <30% blasts (RAEB-T) |

30 |

14 |

5 |

|

CMML |

7 |

1 |

4 |

|

Median blasts (Range) |

13 (0–30) |

8 (0–28) |

5 (0–18) |

|

IPSS-R |

|

|

|

|

Intermediate-1 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

|

Intermediate-2 |

84 |

40 |

16 |

|

High-risk |

70 |

36 |

10 |

|

At least intermediate-2 |

2† |

1† |

|

|

ECOG |

|

|

|

|

0 |

5 |

— |

— |

|

1 |

73 |

— |

— |

|

2 |

4 |

— |

— |

|

Remission status after 5-aza induction (%), n |

|

|

|

|

CR |

— |

8 (10) |

7 (26) |

|

PR |

— |

14 (17) |

8 (30) |

|

SD |

— |

47 (58) |

7 (26) |

|

Other (marrow CR and cytogenetic response) |

— |

11 (14) |

5 (18) |

|

Disease progression |

— |

1 |

— |

|

Sorror index (%), n |

|

|

|

|

<2 |

— |

51 (63) |

18 (67) |

|

≥2 |

— |

30 (37) |

9 (33) |

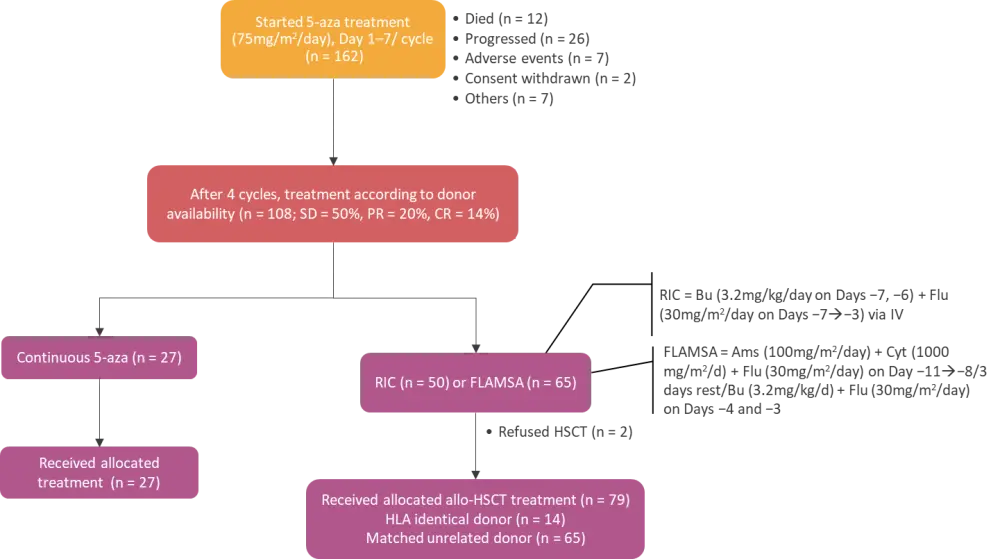

A total of 108 patients were selected and allocated into one of the two treatment cohorts based on the availability of an HLA-matched donor (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study design, patient screening and allocation to respective treatment groups*

5-aza, 5-azacytidine; Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; Ams, amsacrine; Bu, busulfan; CR, complete response; Cyt, cytosinearabinoside; Flu, fludarabine; IV, intravenous; PR, partial response; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; SD, stable disease.

*Adapted from Kroger, et al.1

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS) at 3 years comparing both treatment arms. The major secondary endpoints were comparison of event-free survival (EFS) at 3 years and toxicity and TRM at 1 year.

Results

Adverse events

In the HSCT group, most patients received a stem-cell graft from an unrelated donor (n = 65). Acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) Grade II-IV occurred in 41% and Grade III or IV occurred in 15%. Overall, chronic GvHD was observed in 57% of the patients. TRM was not observed in the 5-aza arm, whereas the cumulative incidence of TRM after HSCT at 1 year was 19% (95% confidence interval [CI], 11–28; P < 0.0065). In the HSCT arm, 13.6% experienced relapse or progression whereas all 27 patients in the 5-aza continuous arm relapsed or progressed during follow-up. There were 14 patients in the continuous 5-aza arm who underwent HSCT (with alternative HLA-mismatched donor) as a salvage therapy due to disease progression. Also, two patients who denied HSCT were moved to the continuous 5-aza arm.

Event free survival (EFS)

The 3-year EFS was significantly higher after HSCT in comparison with continuous 5-aza therapy (Table 2). Multivariate analysis (hazard ratio [HR], 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28–0.94; p = 0.03) and COX regression analysis (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.27–0.77; p = 0 .009) also align with these findings.

Overall survival (OS)

As shown in Table 2, the OS at 3 years was higher for the HSCT cohort compared to the continuous 5-aza group. The difference in OS at 3 years (3.31 years) for the full analysis population—where 14 patients initially treated with 5-aza received HSCT as salvage treatment and two patients who denied HSCT were assigned to the 5-aza arm—was 0.20 (95% CI, −0.11 to 0.50). The estimated OS at 3.31 years was 29% and 49% in the 5-aza arm and HSCT arm (p = 0.3), respectively. The 3-year OS survival was found to be 50% vs 33% (p = 0.5) when patients in the continuous 5-aza arm who received HSCT after progression at time of transplant (n = 14) were excluded from the calculation.

Table 2. Results according to treatment arm*

|

5-aza, 5-azacytidine; AE, adverse event; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; EFS, event free survival; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response; RR, response rate. |

|||

|

Variable, % |

HSCT (n = 81) |

Continuous 5 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Severe AE |

84 |

74.1 |

— |

|

TRM at 1 year (95% CI) |

19 (11–28) |

0 |

0.0065 |

|

EFS at 3 years (95% CI) |

34 (22–47) |

0 |

<0.0001 |

|

EFS at 3 years, (95% CI) interim analysis |

35 (22–48) |

0 |

<0.0001 |

|

OS at 3 years, (95% CI) |

50 (39–61) |

32 (14-52) |

0.1236 |

|

OS at 3 years, (95% CI) interim analysis |

49 (36–61) |

22 (6-44) |

0.0273 |

|

RR, (95%CI) at day 28, CR after HSCT & CR/PR in 5-aza arm |

59.3 (47.8–70.1) |

25.9 (11.1–46.3) |

<0.0001 |

A survival benefit was mainly seen in patients >65 years, in IPSS intermediate II, and in patients in remission (PR/CR) at transplant. A HR of 0.9 (95% CI, 0.49–1.73; p = 0.8) for HSCT vs 5-aza was observed in a multivariate analysis for OS. None of the variables showed a significant impact on OS. Moreover, HSCT as time-dependent covariate in a COX regression for OS resulted in a HR of 0.928 (95% CI, 0.65–1.20; p = 0.78). Six of the 14 who received salvage allografts from mismatched donors were alive at the last follow-up.

Conclusion

Elderly patients (up to age 70 years) with advanced MDS who received HSCT experienced significantly prolonged EFS when compared with patients who received continuous 5-aza therapy. However, the study did not meet its primary end point of a significantly improved OS at 3 years.

Although the OS at 3 years was exactly as hypothesized in the protocol—50% after HSCT and 33% after continuous 5-aza—only a small number (n = 108) of patients could be treated with HSCT or continuous 5-aza, of which only 27% were treated only with continuous 5-aza, as 14 patients in the continuous 5-aza arm subsequently underwent salvage HSCT. Therefore, the study was not appropriately powered to assess the difference in OS as significant and a longer follow up in future studies may show OS benefit.

It was concluded that HSCT should be considered as a potential treatment option for elderly patients with MDS. Nevertheless, benefits of pre-treatment with 5-aza were not clearly identified.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content