All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the MDS Alliance.

The mds Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mds Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mds and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View MDS content recommended for you

“How I treat” case studies incorporating updated classification systems

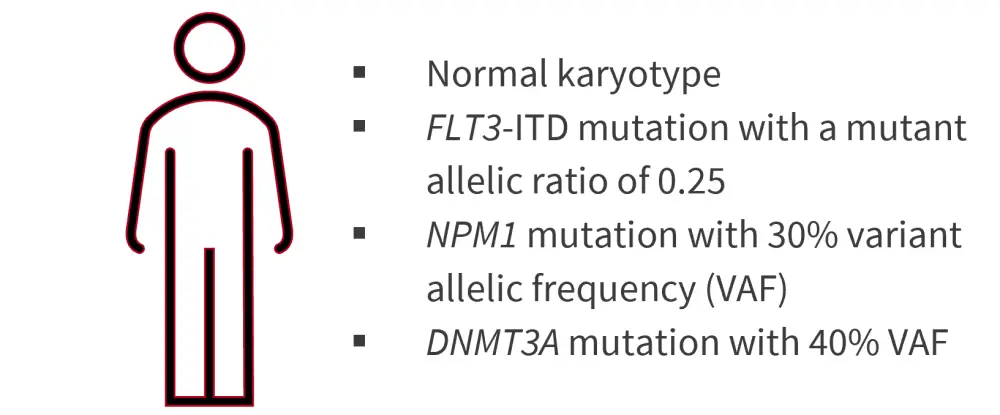

Do you know... How should a patient with 13% myeloblasts, complex karyotype with deletion 17p, and mutated TP53 with a variant allelic frequency (VAF) of 35% be classified under the 2022 International Consensus Classification and the 5th edition of WHO classification?

The “How I Treat” series, published in Blood, provides insight into the diagnosis and treatment of patients, including sample case studies; this series has been previously reported by the AML Hub in relation to new therapeutics. With the recently published 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours, the 2022 International Consensus Classification (ICC) of myeloid neoplasms, the 2022 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) recommendations for the diagnosis and management of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and the 2021 ELN measurable residual disease (MRD) guidelines, the classification, risk stratification, and practice guidelines for AML have changed. Here, we summarize a recent “How I Treat” article by Chaer et al. discussing four case studies, incorporating the recently published classification systems and guidelines along with novel therapeutic approaches.

Summary of the updated classification of AML

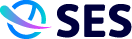

The 2022 ELN, 2022 ICC, and 5th edition of the WHO classification have several key differences, which are highlighted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Clinically relevant differences between the ELN 2022 recommendations, the ICC 2022, and the 5th edition of the WHO classification*

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; ICC, International Consensus Classification; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MDS-IB2, MDS with increased blasts; MR, myelodysplasia-related; PB, peripheral blood; pCT, post cytotoxic therapy; WHO, World Health Organization.

*Adapted from Chaer, et al.1

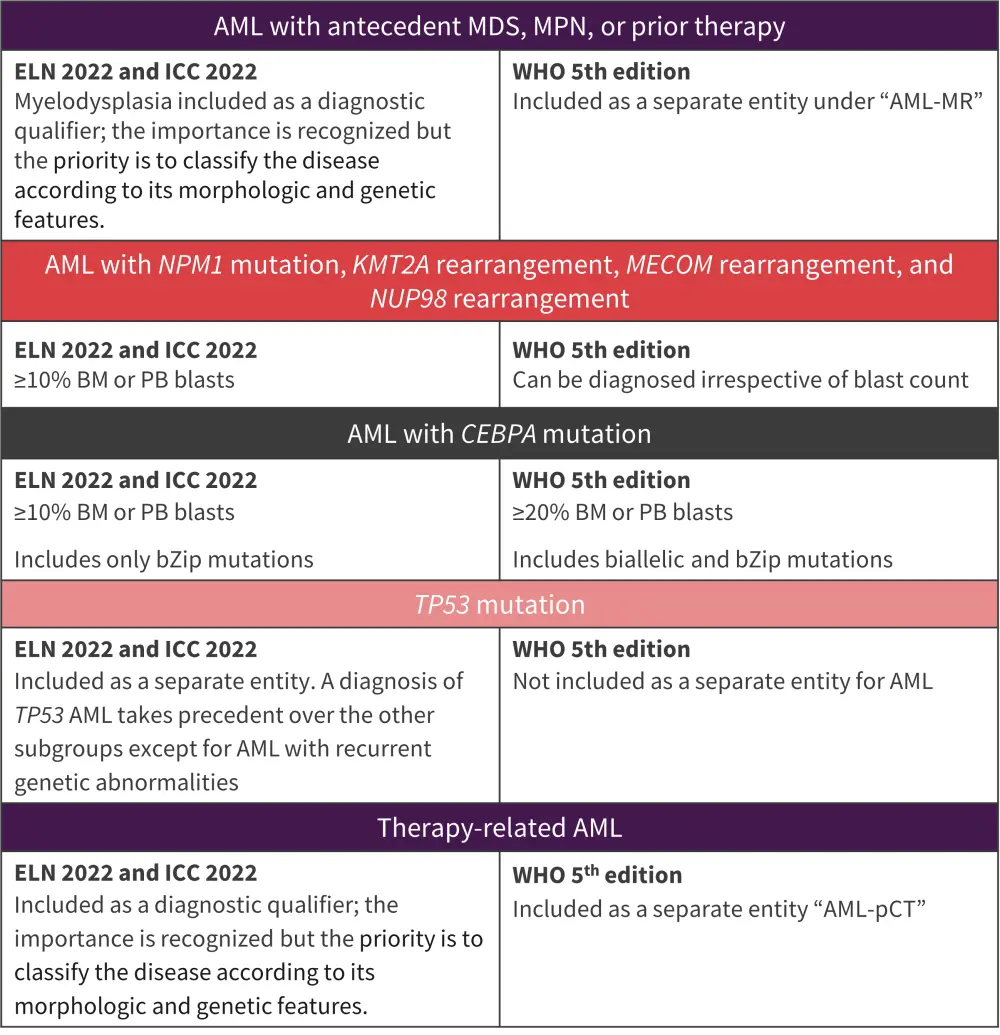

Case 1. 45-year-old male with de novo AML

Figure 2. Case study 1 presentation*

ITD, internal tandem duplication; VAF, variant allele frequency.

*Adapted from Chaer, et al.1

Treatment

- Complete remission (CR) achieved after induction therapy with “7 + 3” and midostaurin, followed by a consolidation cycle with high-dose cytarabine and midostaurin.

- Minimal residual disease (MRD) detected by multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) and molecular MRD assessment using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) detected residual NPM1 mutation in blood after first consolidation cycle.

- No next-generation sequencing (NGS) performed.

- Underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) from a matched unrelated donor after myeloablative conditioning (MAC), followed by posttransplant maintenance therapy with sorafenib (due to the presence of a FLT3-ITD mutation at diagnosis).

- 100 days posttransplant, bone marrow (BM) biopsy showed CR and MRD-negativity by MFC and molecular methods; however, a different DNMT3A mutation with 42% variant allele frequency (VAF) was detected by NGS.

Key points

While this patient would be classified as favorable-risk under the previous 2017 ELN recommendations, the 2022 update now classifies patients with FLT3-ITD mutations as intermediate-risk regardless of NPM1 mutation status, with FLT3-ITD allelic ratio no longer incorporated. The 2021 ELN MRD guidelines recommend molecular MRD assessment over MFC for patients with NPM1-mutated AML, while commercial NGS testing alone for AML MRD is not currently recommended and requires standardization. The guidelines also state that patients receiving FLT3-inhibitors should undergo MRD assessment using alternative molecular targets. The authors commented that, while a DNMT3A mutation was detected posttransplantation, “DTA” clonal hematopoiesis mutations (DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1) detected in isolation at CR are not necessarily associated with relapse; therefore, this patient was considered to be MRD negative at Day 100 posttransplant.

Sorafenib is not currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA), although its efficacy in this patient population is supported by two randomized controlled trials, including the SORMAIN trial.2,3

Chaer noted that, although patients with NPM1-mutated but without FLT3-ITD may be candidates for consolidation chemotherapy (with MRD monitoring for ≥24 months to detect early signs of relapse), allo-HSCT would be recommended in this case regardless of MRD status, due to the presence of FLT3-ITD mutations. Where feasible, MAC is the preferred pretransplant conditioning regimen over reduced intensity conditioning. If transplant is not an option, consolidation chemotherapy with midostaurin maintenance should be considered. The authors also highlighted the need for further research to determine optimal patient selection for allo-HSCT, particularly in patients with intermediate-risk AML, and the role of interventions before, around the time of, and after transplant in patients with MRD positivity.

Case 2. 62-year-old female with myelodysplastic syndrome

Figure 3. Case study 2 presentation*

BM, bone marrow; VAF, variant allele frequency.

*Adapted from Chaer, et al.1

Treatment

- After four cycles of azacitidine, repeat BM biopsy showed 4% myeloblasts and persistence of deletion 17p alongside original cytogenetic abnormalities; VAF of TP53 mutation was reduced to 12%.

- Received allo-HSCT from a matched related donor with fludarabine and melphalan reduced intensity conditioning.

- Remained in remission for 7 months posttransplant, subsequently developing worsening cytopenias; BM biopsy found relapsed AML with 65% myeloblasts.

- Received salvage chemotherapy after condition worsened, but unfortunately died.

Key points

Based on the 2022 ELN and ICC systems, this patient would be classed as having MDS/AML with mutated TP53, due to her blast percentage being <20%, the absence of AML-associated mutations, and a VAF of TP53 mutations ≥10%. However, under the 5th edition of the WHO classification, they would fall under the ‘MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation’ category.

The presence of TP53 mutations has been associated with dismal outcomes. Currently, there is a lack of treatments that specifically target TP53 mutations and more research is required to determine the most effective treatment strategy for patients with mutated TP53 AML and MDS. The AML Hub has previously reported on the outcomes of different therapy options for patients with TP53 mutations here and here. The authors recommend enrollment in one of the several clinical trials currently ongoing for patients with TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies.

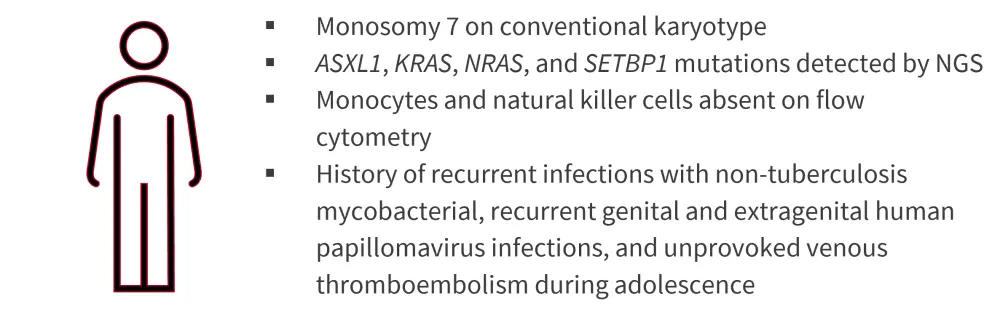

Case 3. 27-year-old female with de novo AML

Figure 4. Case study 3 presentation*

NGS, next-generation sequencing.

*Adapted from Chaer, et al.1

Treatment

- Following CR with intensive induction chemotherapy, received one cycle of consolidation therapy with intermediate-dose cytarabine consecutively on Days 1–3.

- BM biopsy found continued remission and persistence of MRD by MFC and NGS.

- Deleterious germline GATA2 mutation detected by NGS in cultured skin fibroblasts.

- Underwent matched unrelated donor allo-HSCT with MAC (matched sibling donor also carried a GATA2 germline mutation).

- 100 days posttransplant, BM analysis indicated CR with MRD positivity.

- Tapering of early immunosuppressive therapy was initiated; developed gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease but recovered with treatment.

- Remained in CR 2 years posttransplant

Key points

Based on the 2022 ELN recommendations, patients should be screened for a germline predisposition to hereditary myeloid malignancies regardless of age, with family and personal medical histories recorded. The authors commented that while the use of intermediate-dose cytarabine consolidation chemotherapy may improve the rate of blood count recovery and reduce toxicity, this is not supported by randomized prospective clinical trials; patients with favorable-risk AML may benefit from high-dose cytarabine consolidation following “7 + 3” induction therapy.

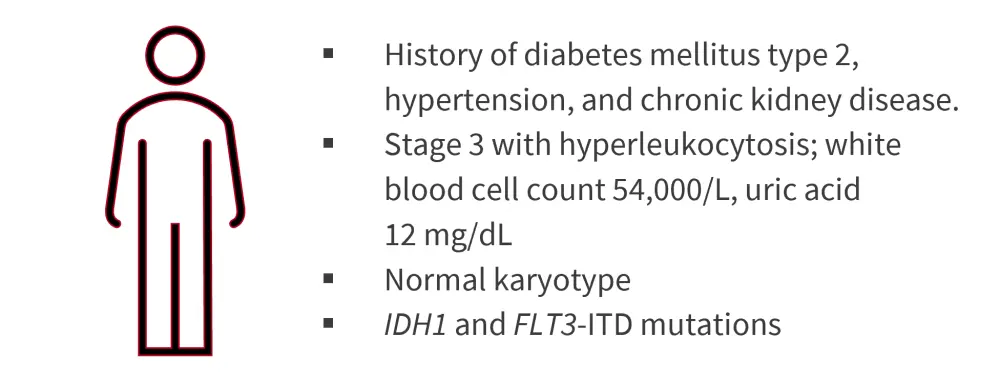

Case 4. 77-year-old female with AML

Figure 5. Case study 4 presentation*

ITD, internal tandem duplication.

Adapted from Chaer, et al.1

Treatment

- Azacitidine and venetoclax chemotherapy initiated at white blood cell count <25000/L.

- CR with MRD negativity was achieved on Day 21 of Cycle 1; however, relapse occurred after 12 further cycles, with presence of IDH1 and FLT3-ITD mutations.

- Received treatment with gilteritinib, and subsequently ivosidenib; however, the disease persisted and the patient died under hospice care.

Key points

Venetoclax in combination with azacitidine has been shown to improve remission rates and confer a survival benefit.4 The authors also discussed a recent phase II study in which azacitidine was substituted with decitabine.5 Early response assessment is recommended for patients treated with hypomethylating agents (HMAs) in combination with venetoclax.

Chaer commented that the current risk stratification systems, such as the ELN recommendations, are based on fit and/or younger patients receiving intensive chemotherapy; therefore, they may not be applicable to patients treated with a combination of a HMA and venetoclax. The authors also discussed a post-hoc analysis of treatment-naïve, intensive chemotherapy-ineligible patients treated with azacitidine and venetoclax, that found patients classified as ELN 2017 favorable- and intermediate-risk had a similar median OS; two subgroups (patients with TP53 and RUNX1 mutations) within the adverse-risk group had a shorter median OS than the rest of the risk group.6 The authors suggested that a modified risk stratification system may be necessary for lower-intensity treatment, and noted that the role of MRD testing has not been fully defined in this patient group.

They concluded that patients with IDH1/2, FLT3, and NPM1 mutations have favorable outcomes when treated with HMAs and venetoclax and that several ongoing clinical trials are investigating HMAs and venetoclax in triplet combinations with a third agent.

Conclusion

The latest classification systems place greater emphasis on genetic factors to define AML and MDS subtypes and in risk stratification. However, differences between these classification systems affect patient groupings, that will vary depending on the system used; this raising the need for coherence between systems. Furthermore, evidence suggests the necessity for a modified risk-stratification system for patients who are treated with lower-intensity therapies.

Novel agents continue to emerge for the treatment of AML with the hope of improving outcomes, particularly in patients with TP53 mutations for whom the prognosis is poor.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content